March 25, 2024

Poppy a new Bloom filter format and open source library

Introduction

At CIRCL we use regularly bloom filters for some of our use cases especially in digital forensic. Such as providing a small, fast and shareable caching mechanism for Hashlookup database which can be used by incident responders.

We initially worked with an existing great project bloom from DCSO as it provided convenient features we were looking for, such as data serialization. To better suits our growing bloom filter needs, we decided to re-implement the bloom project in Rust called Poppy. Over the course of the re-implementation, we have noticed some challenges for our use-cases with the original implementation. Therefore, we have decided to move on towards a new implementation we will detail over this blog post.

So that the reader fully enjoys the content of this blog post, we highly recommend him to familiarize with classical bloom filter implementation.

Reviewing the existing code

At the first sight, when reviewing the original code, everything seems pretty well written. We noticed some minor code optimization that we decided to directly integrate in our Rust port.

After reading again and again the code, we did notice something strange in the bit index generation algorithm (shown below).

// m == 0xffffffffffffffc5

const m uint64 = 18446744073709551557

const g uint64 = 18446744073709550147

// Fingerprint returns the fingerprint of a given value, as an array of index

// values.

func (s *BloomFilter) Fingerprint(value []byte, fingerprint []uint64) {

hv := fnv.New64()

hv.Write(value)

// fnv(value) % m

hn := hv.Sum64() % m

for i := uint64(0); i < s.k; i++ {

hn = (hn * g) % m

// s.m is the size of the bloom filter in bits

// so this computes bits indexes

fingerprint[i] = uint64(hn % s.m)

}

}

Looking closer, this algorithm really looks like a Lehmer random number generator. The only notable difference with documented implementation is the fact that m (used for modulo) is in theory not of the same size as the dividend. For example, if the dividend is a uint64, m is supposed to be uint32.

Another surprising thing is the very high value of m which is uint64::MAX - 58. The surprise came from the observation that doing the modulo of a uint64 with such a big value has a fairly low chance to be effective, as it will almost always return the dividend (except for 58 uint64 on the whole range of uint64). That being said, we decided to implement it this way as we assumed this code correct.

Looking for optimization … getting issues

Everything was going fine, until we looked for further optimization to apply.

Digging into other data structures (like hash tables) implementations, we noticed a nice optimization can be done on the bit index generation algorithm. This optimization consists of taking a bitset (holding all the bits of the filter) with a size being a power of two. If we do so, instead of computing bit index with a modulo operation, we can compute bit index with a bit and operation. This comes from the following nice property, for any m being a power of two i % m == i & (m - 1). It is important to understand that this particular optimization will allow us to win on CPU cycles as less instructions are needed to compute the bit indexes.

Trying to apply this with bloom filter is fairly trivial, when computing the desired size (in bits) of the bloom filter we just need to take the next power of two (not to penalize false positive probability). When implementing this with our current Rust port of the bloom we realized the implementation was broken. When the bit size of the filter becomes a power of two, the real false positive proability of the filter literally explodes (x20 in some cases). Without, going further into the details we believe the weakness comes from the bit index generation algorithm described above. A Github issue has been opened in the original project to track this issue.

We are now quite embarrassed with this issue since to fix it we need to change the bit index generation algorithm. Such a change would break compatibility between versions before and after the fix.

During this optimization attempt, this was not the only challenge we had to deal with, but the following is not directly related to the current implementation. Optimizing filter with a power of two bit size is not ideal, as in the worst case we need to double the size of the filter and we are facing an exponential growth issue. This fact might be negligible when dealing with small filters but no so much for big ones, such as the one (currently ~700MB) generated to hold the full Hashlookup database. In this particular example, we would need to increase the size of the filter to 1GB to benefit from such a speed optimization.

Given those conditions, we had a pretty solid motivation to move towards an improved version of the format, library and tools.

New Implementation: same same … but different

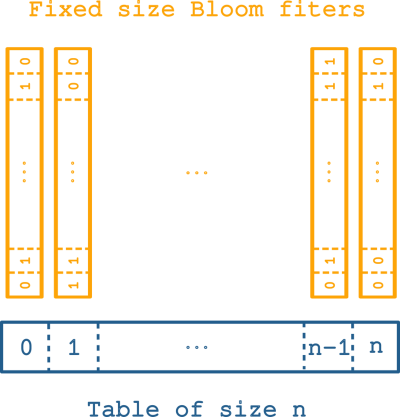

In order to benefit from power of two optimization discussed earlier without bothering about the exponential growth of the filter size we opted for a less common bloom filter implementation. We can see this structure as a hash table containing Bloom filters. It forms an hybrid data structure looking like a hash table but behaving like a Bloom filter. As a consequence we have the same properties (intersection, union) as classical Bloom filters.

To fully take advantage of this implementation one needs to carefully choose the size of the bloom filters. We decided to choose a size of 0x8000 bits corresponding to size of 4096 bytes. This was not chosen at random, on many systems the memory page size is 4096 bytes. So it means that additionally to the power of two optimization we will benefit of another gain in term of memory access. Compared to the traditional implementation, where bits of an entry can be spread over several memory pages, this implementation guarantees that all bits of an entry is contained in a single memory page.

In spite of its advantages, this implementations also has some cons:

- the minimal size of the filter is always 4096 bytes

- we always need to retrieve one filter from memory for a lookup

This is now the time to address the main problem we found in bloom, namely the bit index algorithm. To address this, we opted for double hashing, a more traditional approach seen in other Bloom filters implementations. The only freedom taken on this regard is the hashing function used. The original implementation is using fnv1, which is rather easy to implement but is not adapted for hashing long strings. Fnv family algorithms are processing bytes one by one, impacting hashing performance on large inputs. After several benchmarks, we decided to use wyhash for the following reasons:

- one of the best of our benchmark (maybe for a later blog post). One can see this other hash function benchmark comparing several algorithms

- portable between CPU architectures

- implemented in other languages (important if this work needs to be ported)

In the spirit of providing an improved implementation, we explored some further optimizations applicable to this specific structure.

- one can increase throughput (at the cost of space) by choosing a table size (c.f. structure drawing) being a power of two

- a trade-off optimization (a small space cost but gaining speed) by having a pre-filter bitset keeping track of inserted hashes.

Benchmarks

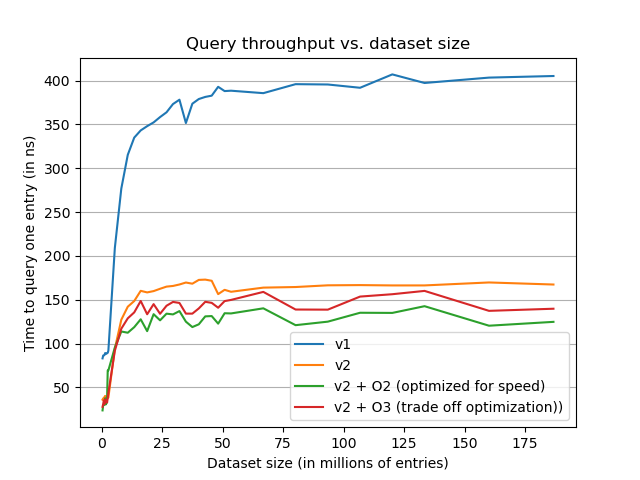

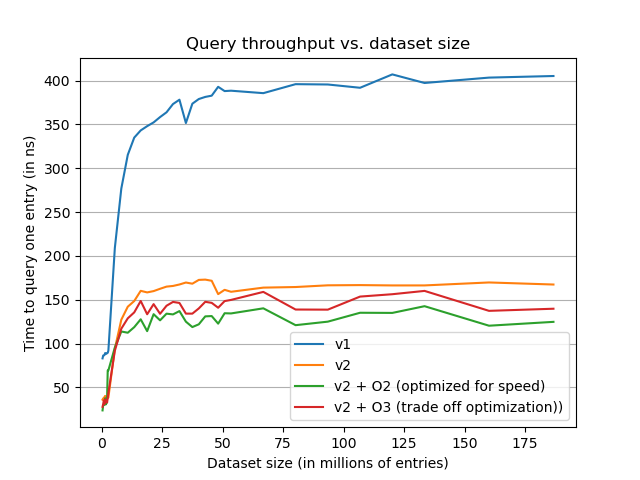

In order to evaluate our modifications and compare it with the previous implementation, we ran some benchmarks on a common dataset. It is worth noting that benchmarking against DCSO implementation (i.e. v1) has been fully done in Rust. Here after, one can find information about our evaluation dataset.

Dataset size: varies between 10MB and 7GB

Data type: sha1 strings (40 bytes wide)

False positive probability: 0.001 (0.1%)

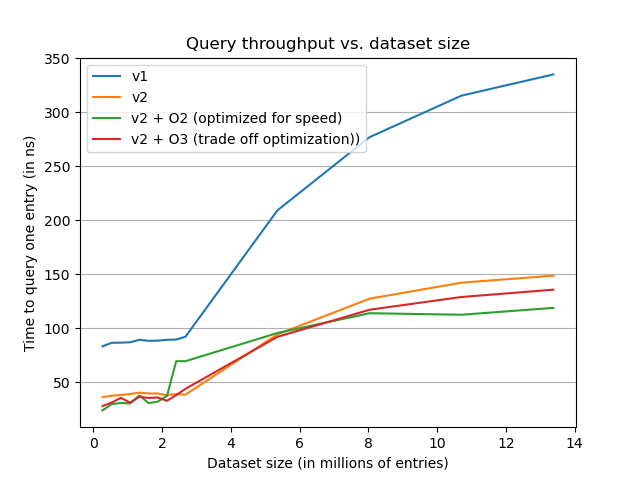

The previous graph shows the impact of the dataset size on the throughput of the filter. We can observe the different advantages of the new implementation. The more obvious is the gain in term of speed ~ 2x faster. The second is that the new implementation is flatter over the growth of the dataset, making it less impacted by always growing datasets such as Hashlookup one.

On the above graph, zooming on the start of the curves, we notice an interesting point, speed optimization might not be good for small datasets. This optimization needs to increase table size to be aligned on a power of two and this increase in size very likely cost more on the memory accesses than power of two is beneficial on CPU. Let’s now take a look at the space impact of the different optimizations.

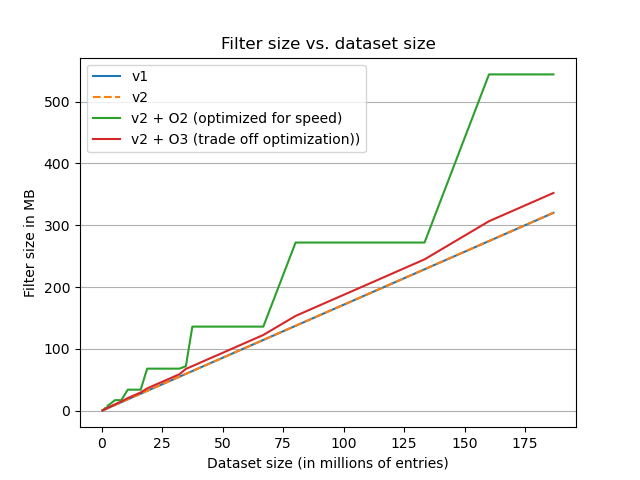

On the plot we can observe that both the implementations (in their un-optimized forms) have the same size. We can clearly see the impact of aligning filter size on the next power of two done by the speed optimization variant. For the trade off optimization, we can observe that size is more linear, making it a reasonnable default choice.

So that Poppy users can compare and choose the best settings for their use case, we integrated a specific bench command. This special command allows to assess the speed of the filter but also verifies that the false positive probability of the filter matches the expected one.

Other minors yet interesting improvements

Creating filters from poppy command line has been implemented to be multi-threaded. It is not much relevant for small datasets but it allows to reduce read/write operations on large filters.

We also eased a bit filter creation over the CLI. Initially, counting the number of entries to set the filter capacity was necessary. Now, entry counting can be done by poppy itself, so the only parameter one has to provide when creating a filter from a dataset is the false positive probability.

# this creates a new filter saved in filter.pop with all entries (one per line)

# found in .txt files under the dataset directory using available CPUs (-j 0)

poppy -j 0 create -p 0.001 /path/to/output/filter.pop /path/to/dataset/*.txt

Conclusions

Lessons learned

Bloom filters belongs to the category of probabilistic data structures which means that many non trivial factors might alter its behavior. Maybe the more confusing aspect about such a structure is that what you get, in term of false positive probability, is not necessarily what you expect. Over the course of this implementation, we had to do many adjustments to limit side effects (such as the one breaking the original implementation). So one wanting to implement it’s own Bloom filter really has to pay attention to the quality of the bit index generation algorithm to make sure it does not create unexpected collisions. The other important parameters is the hashing function used. This one needs to have a low collision rate regardless of the input data. To make sure everything works as expected, thorough testing mixing filter properties and data types is mandatory.

Future work

Poppy is set to become a pivotal Bloom filter library for a variety of upcoming initiatives and projects developed by CIRCL such as MISP Project, hashlookup, AIL Project and many other open source security tooling. This versatile library will be instrumental in numerous areas, particularly in handling sensitive information sharing and threat intelligence correlation, among other applications. The roadmap for the Poppy library includes plans to extend its capabilities, allowing for network access to the Bloom filter. We also invite external contributors to join the project, bringing new ideas and enhancements.

References

Acknowledgement

The Poppy open source project is developed in the scope of the NGSOTI project and co-funded under Digital Europe Programme by the ECCC (European Cybersecurity Competence Centre and Network).

The NGSOTI project is dedicated to training the next generation of Security Operation Center (SOC) operators, focusing on the human aspect of cybersecurity. It underscores the significance of providing SOC operators with the necessary skills and open-source tools to address challenges such as detection engineering, incident response, and threat intelligence analysis. Involving key partners such as CIRCL, Restena, Tenzir, and the University of Luxembourg, the project aims to establish a real operational infrastructure for practical training. This initiative integrates academic curricula with industry insights, offering hands-on experience in cyber ranges.